The days and nights of rolling around in the trenches and dancing on the skyscrapers of the city seem long gone.

The epicenter of the city is going up, up, up, but the streets are drenched with exhaustion and other unmentionables. Spirits are low. Is that blood, feces, or water on the floor? People are tired. People are broken. People are dangerous.

Still, I circle the Financial District over and over again. I refuse to pay for parking. I’m from here.

Finally, I see it, a slightly illegal yet otherwise unmarked open space, close enough to a 2 hour parking sign for me to make a case.

I cross my fingers and cross the street on Grand and 7th, making my way towards Olive Street, where Wönzimer sits tightly nestled between an old cafe with an umbrella eyelid and a liquor store that blends into vert maurin marbled walls. In the shadow of the historic Oviatt Building, the gallery’s stately facade smiles coyly at passersby just a few hundred feet away from Pershing Square.

I am warmly welcomed into a pleasantly ambiguous room packed with past lives: a grandfather clock, a pair of mosaic patio chairs, oriental rugs, records, victorian couches, and an archaic chandelier seem to embrace the incoming crowd. But of course, this is the living room.

Beyond it is a door posing as a bookshelf.

I walk through it and into Salon De Imperfectionism, instantly intoxicated by the harmonious balance of chaotic chatter and inanimate objects. I find myself in an open ocean of mini-worlds, portals, germinations, and ripened fruit; but three works anchor me.

Courtesy of Wönzimer

El Cuerpo is one of Sinclair Vicisitud’s latest works. The title may allude to the body of the work, the body of the earth, the uprooted bodies in the landscape, or the collective body, including mine, as my hands instinctively reach towards what appears to be a painting made of raw earth. As a brown body moving through a digitized world, the work excites me like a child playing with the elements for the first time. Yet, there is a tension that occurs between creation, destruction, and reflection all taking place at once. The seeds are planted but the rows are bare. Rather than witnessing life bloom, we observe bodies discombobulating. Limbs mimic parched desert plants. Explosions at a distance could be mistaken for the setting sun. Is that a floating head, screaming in the woman’s ear? If it is, let us hope it is the tyrant’s final cry.

Though worlds apart, the pathos of the work is reminiscent of Jean Fautrier’s Hostages series, which he began in 1943 while evading Nazi authorities in France. Rather than explicit figuration, Fautrier captured the atrocity of the times through his brutal application of materials in producing works such as Tete d'Otage no. 1, 1944 and Dépouille, 1945. In El Cuerpo, a similar erosion, exhaustion, and violence pollutes the image, especially where geometry collides with primordial life, attempting to impose order. In the top left, the texture and trauma of the application is intensely pronounced within the pseudo-digital cloud that hovers but provides no shade. At the same time, the coloration is not unlike that of a dying earth from the point of view of space. Land, bodies, forests, fires, jungles, and boiling waters blur into one another on the hot, hot planet before drying out completely. In the top right corner, algorithmic vines creep eerily from the scorched land, bearing weeping fruit and berries with sad faces. These vines recall the linear abstractions birthing ambiguous anthropomorphs in Lari Pittman’s An American Place, which was produced at the height of the AIDS crisis. All works beg the viewer to acknowledge the insidious violence consistent in our bodily lives in the past, present, and future.

The face of the mother is like the berries, but her anguish is immensely deeper. She is aware of her own suffering, the suffering of her child, and of dying mother earth. One can only assume the face of the child bears a deeper agony as they return the gaze of the mother, but we cannot know for certain, and serendipitously, it raises a question. Not who are they, but what will become of them? The mother, quite literally with her hands tied behind her back, appears tortured by her inability to further sustain the life around her. And the child? Hope may be derived from the universal fact that while some children become ruined, some become survivors, and others become healers.

And if you look closely, past the extinction of our collective corporeality, in the very center of the pain, we see amongst the pillaged land, what might be a microscopic glance at the past, before the earth began to burn, when mother and child sat peacefully side by side in a warm embrace. Let us hope it is not the final glimmer of the world we once knew, but a lingering seed for the future.

~

Sam Valdez’s textile demonstration, Remember, is a flag purged of nationalism, a blanket for an entire continent, a handwoven nest for humanity, and an architectural blueprint for the future. Gathered organically over time, the fragments of fabric have been pulled apart, ripped, and essentially destroyed before the artist rearranges them once again. As the threads come loose, their individual textures and forms are set free, disentangled from perfect symmetry, before being gently woven into a new visual narrative by maternal hands rather than tools of mass production.

The newborn forms hardly recall any one specific lineage, cultural aesthetic, or geographic style. Instead, the rectangular section of green that has been placed in the center mimics the architectural blueprints of antiquity. Unafraid to take the leap, I contend that the softened, central geometric forms are not unlike the shapes expressed in aerial detail of the Roman Pantheon, should the dome have been surrounded by extended porticos on either end. The comparison is not superfluous; instead it emphasizes the capacity of the feminine divine to invert and reinvent, seen here at play, especially when considering how textiles and architecture often exist at opposite ends of the the gender binary that suffocates modern society.

Valdez’s seemingly silent flag is actually confronting the entire theoretical foundation of white supremacist patriarchy. The Pantheon, an architectural display of the ancient brotherhood, a physical instantiation of the legacy of global patriarchy, now mirrors in form with the nameless, the dying, and the disappeared women who dared nurture the wounds of the world, their voices woven together and revitalized in Valdez’s narrative textile.

This is not unlike Hito Steyerl’s demystification of the connection between missing women and macroscopic or physical infrastructures in her presentation Is the Museum a Battlefield?

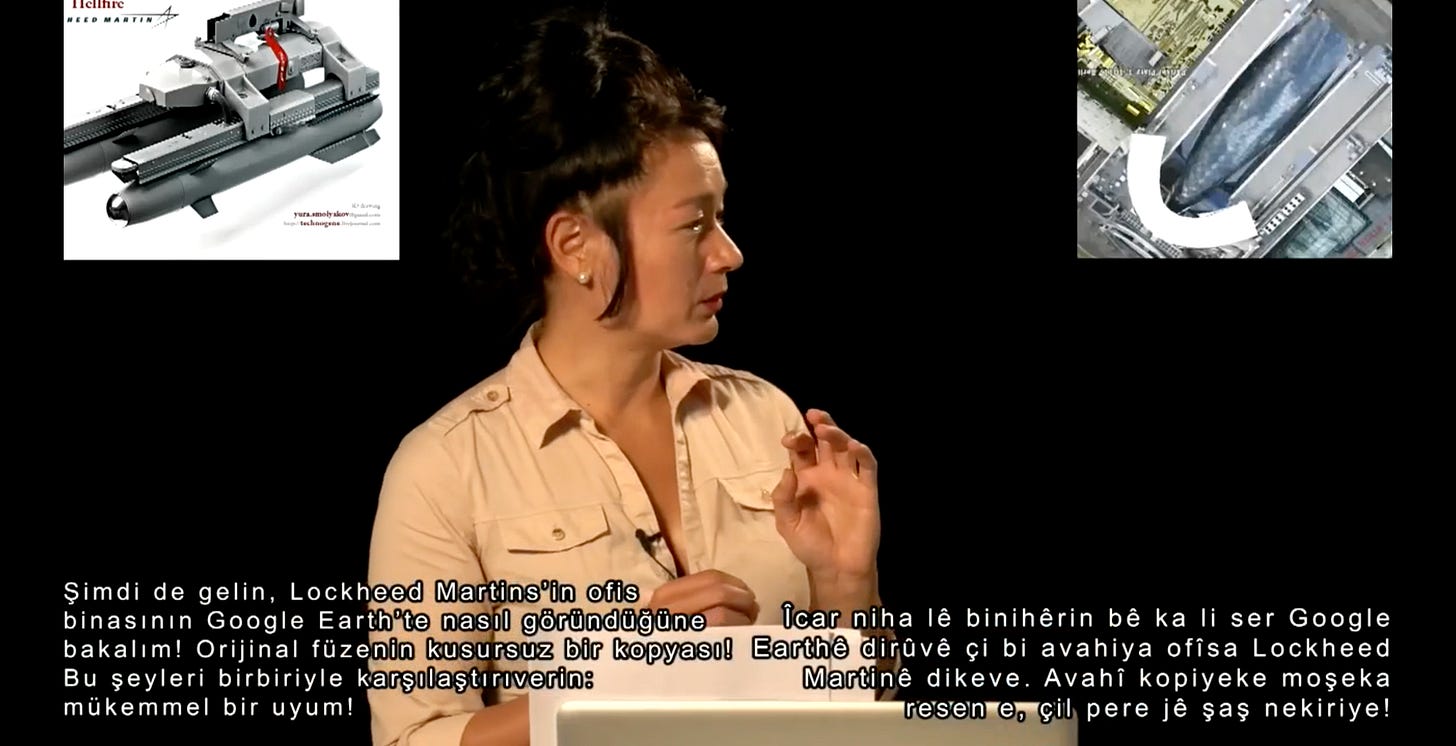

Steyerl traces the trajectory of war debris from obscure execution zones, to museums, to the starchitecture of western metropolises. Steyerl states, “When following a few pieces of debris back to their makers...back to the places they were launched from initially…,” she discovered that Lockheed Martin’s Hellfire missile, launched from a Cobra helicopter, is the exact same shape as the Lockheed Martin headquarters, designed by none other than Frank Gehry.

Steyerl manages to identify bizarre facts, formulate uncharted theoretical systems, and locate empirical connections to the concrete world. Likewise, in Remember, Valdez does this instinctively, through the act of nurturing, nesting, and reviving orphaned pieces of fabric. The resulting artworks, though diverse, both become spiritual-physical spaces in which the artists mourn, confront, and recreate the past in real-time with their bare hands. Valdez’s process goes beyond mere destruction and creation, in that she is literally reprogramming a narrative that affects every living body by re-weaving an amalgam of artifacts, and in doing so, critiquing and dissolving the credibility of the western colonial patriarchal project. In considering Valdez’s long-standing position as a national activist, the piece is also a contemporary ode to embroidered suffrage banners, only without the traditional linguistic constraints.

~

It’s My Wedding Day by Julia Nejman is a self-erected statue, a self-portrait, a throne for one’s blood and pain, a celebration that borders self-sabotage, an act of bondage and liberation, and a performance that outlasts itself. Interestingly, here too, a critique of ancient western culture proves insightful. In contrast to the clean, naked marble bodies championed in colonial institutions disguised as museums, Nejman’s body of work demands that its inner turmoil be seen from the outside in. A physical interconnectedness constricts the work and its surrounding environment. The ripped, weathered, and warped wedding dress resembles intestines, spider webs, soiled hospital linens, homeless tents, and the beltscarves found in execution zones in the south of Turkey (where Steyerl’s friend Andrea Wolf had been extrajudicially executed in 1998 for being a member of the women’s section of the Kurdish Workers Party.)

Yet again, we observe works that are worlds apart, yet born of the same wound. In each unique circumstance, the debris begins to look the same. Back at Wönzimer, the tail of Nejman’s dress is tethered to the room’s support beam. Once again, the symbolic proves inseparable from the biological, structural, and architectural components of a failing society. Once again, women bear the weight of a lethal paradigm they did not consent to.

Executed in three acts, Nejman’s work revolves around themes of marriage, ownership, and captivity, as exemplified by the web-like constraints. These themes, these networks of oppression, are the foundation of the western colonial project, as recapitulated in Friedrich Engels’s late work, The Origin of the Family, Private Property, and the State1, in which he traces the conquest of the female species through the act annihilating the human tendency towards matriarchy, by replacing it with paternal lineage:

“The overthrow of mother right was the world-historic defeat of the female sex.

The man seized the reins in the house also, the woman was degraded, enthralled, the slave of the man's lust, a mere instrument for breeding children.

This lowered position of women, especially manifest among the Greeks of the Heroic and still more of the Classical Age, has become gradually embellished and disassembled and, in part, clothed in a milder form, but by no means abolished.

The first effect of the sole rule of the men that was now established is shown in the intermediate form of the family which now emerges, the patriarchal family…

The essential features are the incorporation of bondsmen and the paternal power; the Roman family, accordingly, constitutes the perfected type of this form of the family.”

Engels points to Marx’s observations on the Greek Family:

“While, as Marx observes, the position of the goddesses in mythology represents an earlier period, when women still occupied a freer and more respected place, in the Heroic Age we already find women degraded owing to the predominance of the man and the competition of female slaves…

True, in the Heroic Age the Greek wife is more respected than in the period of civilisation; for the husband, however, she is, in reality, merely the mother of his legitimate heirs, his chief housekeeper, and the superintendent of the female slaves, whom he may make, and does make his concubines at will. It is the existence of slavery side by side with monogamy, the existence of beautiful young slaves who belong to theman with all they have, that from the very beginning stamped on monogamy its specific character as monogamy only for the woman, but not for the man.

And it retains this character to this day.”

Therefore, Nejman’s performance ephemera, like Valdez’s orphaned textile blueprint, becomes an anti-monumental, unraveling set of threads that trace the roots of patriarchy and ownership back to their western foundations. Despite the perpetual threads of oppression, Nejman is able to reclaim, revive, and self-fashion their identity outside of the legacy of white supremacist patriarchy by creating a work that gives birth to itself violently, again and again. The inner world spills loudly onto the dress, refusing to be clean and still in the shadows of history. Instead of a virginal body draped in pure silk, the artist presents a body that refuses to swallow its rage and gazes at the viewer without eyes. The blood pours. It speaks. Below the statue, the final act titled Soul Arrangement shows the world what it refuses to see: the collective wound spilling from between the legs of every woman.

Salon De Imperfectionism is on view until August 11, 2021.

See pages 734-751